-

Posts

2,579 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Donations

0.00 USD

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Blogs

Everything posted by ep1str0phy

-

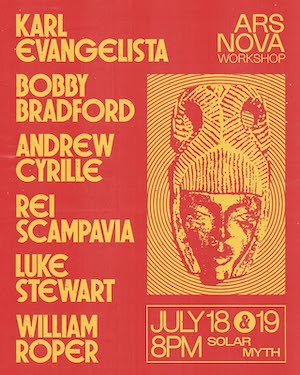

Hello, all- I'm not sure how many of you live near Philadelphia, PA, but these shows are going to be an event. On July 18-19, I'll be in residency at Solar Myth in Philadelphia (courtesy of Ars Nova Workshop). I'll be joined by the insane company of masters Bobby Bradford and Andrew Cyrille, as well as LA tubaist William Roper, bassist Luke Stewart, and Grex mate Rei Scampavia. This project had its genesis in the California wildfires earlier this year. As you may be aware, Bobby and Roper lost their Altadena homes. In the process of our relief effort, the idea arose to reunite Bobby and Andrew - two veterans of John Carter's Roots & Folklore saga. These dates mark the only occasion that the two of them will have played together in several decades, as well as Bobby's first appearance on the East Coast in some time. (Bobby actually turns 91 that weekend!) Appropriately, I'll be presenting a brand suite piece of music - "Taglish II," which explores the Filipino-American experience in 2025. It revisits some of the themes and character of John Carter's music, although the sonics of the piece are squarely contemporary. Tickets are available HERE More Info: https://www.arsnovaworkshop.org/programs/karl-evangelista-bobby-bradford-andrew-cyrille-rei-scampvia-luke-stewart/

-

Thanks for sharing, Alex! I know it must be tough to put this into words. Contextualizing this in terms of a formal breakdown of a performance is a brilliant touch.

-

Hooker/Braufman/Lewis June 26 @ Tubby's Kingston

ep1str0phy replied to clifford_thornton's topic in Live Shows & Festivals

This looks like a blast, man. I didn't even know about the reissue - excited to check that out. -

Thanks for the kind sentiments, all. These circumstances are sad, but I hope that they provide an opportunity for people to revisit (or discover) Louis's music. I mean this with all sincerity - IMO, Louis was always at his best in Alex's company. Keep Your Heart Straight as an all-timer, and it stands out even among the many brilliant piano-drum duets that Louis essayed. Uplift the People is similarly masterful, and the seemingly indefatigable power of Louis's drumming on that record must surely rank among the best of his later career. Clifford, I'm assuming you're familiar with the Old Stuff record on Cuneiform? It's the same band that appears on the America record. There's a version of "Rosmosis" on Old Stuff that is just unbelievable - a testament to how Louis could make a meal out of these repetitive, trancelike grooves. Having been lucky enough to know both Louis and Milford, I'm not an objective observer of this music - but their wildly different approaches service the music in profound ways.

-

I owe an awful lot to Louis. He’s one of a special handful of my childhood heroes whom I met and liked even more. He was doggedly invested in the idea of art as a form of resistance, and he played accordingly. There was an intention and directness behind his drumming that was uncanny, and it forced the burdens of the real world to retreat into chasms of sound. He seemed to master things like pain and injustice with the power of his sound. And he made it seem like so much fun that from the moment I met him, I wanted to be just like him. Music saved me from a desk job, and Louis saved me from only wanting to be around music. His lived experience as a rebel against Apartheid, manifesting his art as this noble struggle against bullies and tyrants, resonated with me completely. At times such as now, it’s so easy to feel directionless and impotent. Louis’s music taught me that you can never lose the battle so long as you continue to fight, and constantly. Louis also helped me to resolve some internal contradictions with my own identity. As a Filipino American, I have often struggled with the fact that I am spiritually Filipino and yet American in temperament and mind. Louis had a visceral commitment to abstraction that was paradoxically couched in his love for South African tradition. Everything was The Song. As soon as I understood this, it became easier for me to be myself and yet wholeheartedly the son of my ancestors. I only met Louis on a handful of occasions. The brilliant and indispensable Alexander Hawkins reconnected us. In 2018, I journeyed to London to record an album called “Apura!” (released in 2020 on Astral Spirits). This record may have been Louis’s last chronological recording, although a wonderful record with Bay Area powerhouse Patrick Wolff - recorded only a few days before “Apura!” - came out in 2024. You have to understand, Louis was/is my hero. My favorite musician. So when the opportunity for this session came up, I practiced for 3, 4, 5, etc. hours a day for over a month. I practiced solo. I practiced along with recordings. I set up sessions with friends and gigged constantly. I think I could play like 60% of all Blue Notes songs cold. I practiced so much that I credit this session with helping to me to develop a clear sonic identity, which I don’t think I truly obtained at until the lockdown era. When I arrived at the session, the first thing I heard was Louis’s cymbals. They have a shimmering, eerily distinctive sound. When I sat down at my booth, I realized that Louis wasn’t using sizzle cymbals. He had taken a few pence and just laid them, unsecured, on his rig. They were like this for the full two days that we recorded, and I watched them fall countless times. As we played, it slowly dawned on me that the practice I had done had not actually prepared me for the session. True and natural free improvisation requires a degree of flexibility and intuition that you can’t arrive at with woodshedding alone. Louis was all improvisation. He even improvised his cymbals. Every day, I strive somehow to be the way that Louis was. To play naturally, like a heartbeat. Louis helped to restore me to the person I actually am, whose ancestors farmed and fished, fighting colonialists and fascists in the sugar cane fields. I may not have known Louis very well, but I do know that he’d be proud of anyone continuing the struggle that he once led - especially other musicians. Louis, Dudu, Mongezi, Mbizo, Chris, Nik, and their kin are reunited now, and they will continue to teach us so long as there are people willing to learn.

-

Mccoy Tyner and Joe Henderson live at Slugs Saloon (Blue Note)

ep1str0phy replied to ghost of miles's topic in New Releases

I just got to this record, on the recommendation of a trombone player friend who talked it up on a gig. My CD purchasing habits took an absolute nosedive at the onset of the COVID era, so I didn't even realize that this had been released. I find the narrative behind this music really fascinating. The Iverson article is simultaneously deeply literate and hermeneutical in kind of a weird way. I wouldn't go as far as to call it revisionist, but it feels like part and parcel of this latter-day obsession with mythmaking that suffuses a lot of modern jazz writing. The valorization of certain figures that resonate with 21st century pedagogical or critical worldviews just strikes me as unnecessarily ideological. All of us who came of age after the heyday of this music are receiving its knowledge secondhand. I'm very leery of writing that cordons specific artists or styles into rival or contending scenes, in part because these barriers are almost always invented after the fact. I highly doubt that someone like Jack DeJohnette was thinking, "now I'm free jazz," "now I'm inside-outside," "now I'm fusion" while he was making the music. This just flies in the face of how rapidly and inscrutably this music was developing after 1960 or so. And so there's something weirdly ahistorical and sensationalist about propping this music up while simultaneously underplaying just how complex the music emanating out, for example, the Survival Records label was. Forces of Nature is really good, but its obvious stylistic reference point (from a 21st century, recorded-media-as-bible standpoint) is the Coltrane Half Note tapes. And I feel like a release of this kind, if we're talking as writers/listeners and not "the cats," needs to be contextualized inside of '65 Coltrane. Weirdly, I don't think there's much more nuance than that - this is epochal music that just so happens to be invoking the praxis of even more epochal music from literally one year prior. Which is largely immaterial to the discussion at hand - except to the extent that we're talking about the Joe Henderson of this vintage as some kind of appendage to the liminal "out" music of the Coltrane lineage. And Henderson is just not an out musician. There's like no recorded evidence that Henderson could use the language of free music in a facile way. His use of multiphonics, bent notes, etc. is just an extension of his riffage. He never really goes out of time, and he almost always resolves his bursts of "chaos" with blues or bebop vernacular. You can hear it all over "Taking Off." In this way, the band uses the ethos of Trane, even though Joe himself has nothing to do with Trane. I'm not passing judgement, BTW. I really enjoy this release and freely admit that I could benefit from listening to it more. But I feel like there's this constant push in jazz writing to prop up historical documents - sometimes in disingenuous ways. And doesn't it better suit the music to say that this was just four of the cats playing their shit, rather than some heroic act of radical invention?- 108 replies

-

- mccoy tyner

- joe henderson

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

If I'm looking at this in a clearheaded way, Andre probably thought that this was just a cool curiosity. His publicity/manager/etc. thought that it would be a good way to drum up visibility. I can't imagine that he anticipated any sort of blowback. I don't know Andre, I don't know his mode of thinking in this case, so all of this is purely speculative. But he seems to be squarely situated in that stage of his career where he'd rather be regarded as an artistic figure or creative doyen than a hip-hop icon. I mean, more power to him, but his hip-hop career was already a perfect container for exploration. The Love Below had a drum and bass version of "My Favorite Things," and it's spectacular. Producers like Madlib or itinerant drummer Karriem Riggins do random jazz/improv shit all the time. Kendrick was rapping over modern straight-ahead jazz on To Pimp A Butterfly. You can operate outside of the strictures or even pressures of your genre and still give maximum effort. It's really the laziness of all this that has been raising so many hackles.

-

And maybe he didn't. I knew him, but I can't pretend to know what he was thinking. His career is kind of an object lesson in how not all art shares the same goal. Andre 3000 wanted to make a splash at the met gala. Milford was trying to teach something. Everyone needs money, but not everyone wants it for the same reasons. I can feel negative about the state of things, but I can't afford to be pessimistic. That's purely a matter of personal exigency, and I understand the opposite impulse.

-

Let me put it this way: Hunter Biden is a way better painter than Andre 3000 is a pianist. It's to the extent that it feels like a social experiment of sorts. I appreciate the perspective - sincerely. There are some phenomena, like the deal with this record, that are so mind boggling and dumb that feel manufactured precisely for this moment in history. One of the few things that gives me comfort at this time is hearing stories about the old heads - about how Sunny Murray had to take it upon himself to serve as Eric Dolphy's bodyguard, because Eric was constantly under threat of assault, or about how Milford Graves still had piles of unsold IPS records sitting in his back room around the time of his passing. I think that things are baldly desperate right now, but not necessarily more desperate than they were/have been. This dust up about Andre 3000's record will just be grains of sand on the beach when all is said and done.

-

Exactly. If you're going to invoke the name of Thelonious Monk, and you are a music writer, you have some obligation to explicate the ways in which the work in question relates to Monk. Is Andre a virtuoso pianist? Is he a hobbyist? Does Andre have an actual grasp of harmony, or is his work more intuitive? Is there a gap in terms of quality, artistic accomplishment, or cultural relevance? Like, you don't have to answer these questions as if you were writing a dissertation. But maybe exercise a bit of self awareness beyond, "hey, this sounds like Thelonious Monk." The articles about Shipp have been crazy, too. They're treating Shipp as if he's indicative of some kind of jazz orthodoxy, which conveniently underplays the very real fact that Shipp has spent his entire career participating in fringe music. The headline in these instances is that "Jazz Pianist Doesn't Like Andre 3000" - which is utterly devoid of nuance. This is one of those situations in which the machine of the music business seems glaringly, stupidly transparent. It's been a bunch of bad-faith hot takes and very little responsibility in terms of representing art in an honest and clearheaded way.

-

I had to log in just to see what the line was on this thing. I say this as someone with a deep love of hip-hop and avant-garde beat music - I think it's a bad record. At the same time, I'm more troubled by the response to said record than I am the content of the album itself. I'm strongly of the mind that these self-indulgent novelty records aren't a bad thing, at least in an intrinsic sense. A good point of comparison is Kid Cudi's Speedin' Bullet 2 Heaven. That album was universally derided. It's objectively a mess of amateurish musicianship and tonal inconsistency, but it's also one of my favorite concept albums. It somehow manages to say something revealing about the artist, and it does so with ugly, confused sincerity. It's a project that deserves to exist, despite its aggressive lack of coherence. If Andre 3000 had just farted this thing out on Bandcamp, it would have been totally fine. Everyone does this these days. What's preposterous about the whole thing is that it's clearly part of a quasi-publicity stunt, timed with Andre's appearance at the Met Gala. He and his team are actively using his celebrity to push the visibility of an artistically malformed object. I try to find virtue in everything, and I'm not so precious about my first steps into this music that I forget how much of my own output represents a work in progress. But these piano pieces are just bad. Like straight up bad. They're technically inept and unfocused, without any clarity of vision. Worse still, they sound unfinished - unmixed and unmastered, lazily sold as "sketches." The thing feels like an elaborate troll - which, if that is the case, then I take back everything I said. Job well done. Andre can do whatever he wants, obviously. He's a celebrity whose fumbling efforts at art music have an admitted element of sincerity. But what makes this thing so egregious is the mass delusion that has followed in its wake. It's been nonstop critical plaudits and (bemused) admiration from casual listeners. I kind of feel like the only people who have actually been complaining are actual art musicians in the tradition that Andre is mining, like Shipp. And it's not a matter of jealousy - not entirely, at least. If I'm understanding Shipp correctly, it's not that people want Andre's listeners for themselves. They just want acknowledgement that the work has an objective reality, and that there are metrics and criteria for even considering the continuum of Black music, art music, etc. that supersede short attention spans and faddish dilettante-ism. Because most of the listeners who grab this thing will never listen to Shipp, but it's not as if Andre seems to care about that problem one way or another.

-

Solace Angles, feat. Bobby Bradford and William Roper

ep1str0phy replied to ep1str0phy's topic in New Releases

Thanks for your support, all! See you there, Steve! That gig is going to be nuts - Andrew and Bobby haven't played together in a long time, and the fires in LA prompted us to put something together. I'm really excited about the music. -

Solace Angles, feat. Bobby Bradford and William Roper

ep1str0phy replied to ep1str0phy's topic in New Releases

Hey, all - just in case you missed this one, it's out today- Available on Bandcamp: https://karlevangelista.bandcamp.com/album/solace-angles And from Asian Improv Records: https://www.asianimprovrecords.com/product-page/air122-d All the best to you all, K/ep1 -

Hello, all - I figure a few of you may be interested in this brand new album, releasing April 15 on the venerable Asian Improv Records. The release in question is called Solace Angles, featuring the mighty cast of Bobby Bradford, William Roper, and my Grex mates Rei Scampavia and Robert Lopez. Solace Angles is a tribute to Los Angeles - a place I love dearly, and that has needed dear love as of late. Recorded in 2023, this recording is the culmination of a longstanding ambition of mine to record an intergenerational document of West Coast free improvisation. It touches on elements of Bobby's collaborations with the great John Carter, with shades of the seminal trio Purple Gums and the daring, open-ended work of Nels Cline and many others. In the interim between recording and release, Bobby and Roper were both impacted by the 2025 greater Los Angeles wildfires. (You may have caught wind of our fundraisers.) It was never my intention for this recording to engage with that tragic event. Rather, I'd like to think of Solace Angles as a celebration of West Coast free improvisation at its most resilient. Pre-orders and a representative preview track are available now at https://karlevangelista.bandcamp.com Thanks to all! K

-

Hi, Adam - sorry I missed this! Quite anxious about the coming week, but I'm hoping that the heightened state of preparedness means that the worst stretch of danger is over. Let's absolutely connect on FB (if you need help finding me, just DM me). There is a story to be told about everything that has transpired in the past few weeks, but I take some heart in knowing that the music community has done a tremendous job of taking care of its own. Bobby and Roper will land on their feet - I think it's just a matter of triage right now, on top of the incalculable personal loss.

-

I meant to post this in Bobby and Roper's thread, but I might as well add here- This is a master list of active resources and gofundmes related to the fires. If anyone wishes to help musicians who have been affected, this is a good resource: Support The Music Community - Fire Loss Funding

-

Adam, that was my post! I'm so glad it's making the rounds. I hope you and your home stay safe. In the past few days, I've had countless conversations about the state of things in LA. There are demographic, cultural, and optical factors at play that are just depressing. But the outpouring of support in the midst of this crisis has been truly astounding.

-

On top of the personal loss, the destruction of all that vinyl is devastating. On a brighter note, the sheer volume of people who have reached out with offers of aid is truly humbling. Music people take care of music people. It's a truly beautiful thing.

-

Thanks to all of you for your thoughts, kind words, and consideration! Lest it go unsaid, I'm happy for others to post any and all fundraisers for other musicians. It's an extremely chaotic situation. To those not attuned to the situation, Altadena was a musicians' haven of sorts. According to my understanding, about half of the area was burned down. The personal loss is immense, and we also lost a tremendous amount of history. Bobby's home alone was a storehouse for a lot of things that the jazz and creative music worlds will sorely miss. Any and all help is appreciated. As far as I can tell, basically all of the fundraisers have been run by friends and other musicians. Only hands can wash hands, etc. If you're in or near LA right now, please stay safe. And much love to everyone.

-

Hello, all- (Apologies in advance if this thread seems inappropriate for the artists subforum) Long story short, Bobby Bradford and William Roper - two LA creative musicians whom you may be familiar with - recently lost their homes in the 2025 LA wildfires. About half of Altadena was destroyed, and countless musicians were affected. Bobby actually lost his horns, escaping only with the clothes on his back. We have started two (official) fundraisers to help the aforementioned gentlemen get back on their feet. Contributions are of course extremely welcome, but any help spreading the word, etc., would be hugely appreciated. Bobby: https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-bobby-bradford-rebuild-after-wildfire Roper: https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-william-roper-rebuild-after-wildfire All the best, K/ep1str0phy

-

I was just about to post this- I enjoy this recording. W/regard to your point - although I think that Barron acquits himself well, it also sounds like there's a bit of a remove there. Barron very much strikes me as a post-bop cat who was fluid enough to hang with open structures. But Cecil's music is rooted in motivic interplay (e.g., the unit structures thing), which almost necessitated the invention of a new idiom on multiple instruments. It's the fine line that separates Jimmy Lyons from Ken McIntyre or, speaking in broader terms, Andrew Cyrille from, say, J.C. Moses. Speaking in pure hypotheticals, this is the kind of free idiom that I can see McLean getting close to. Late Coltrane had a constant (if not static) rhythmic engine, which is at odds with the momentum-oriented playing that McLean excelled at. I can imagine McLean slotting into the Lyons role well, especially if supported by a drummer as literate as Cyrille.

-

Hello, all- I figure that this one may be of interest - our mutual friend Alex Hawkins is going to be visiting the Bay Area next week. We'll be playing some of my compositions + free improvisations, and the bands are fantastic. In the off chance that some O board longtimers are out west, it might be worth the visit. Hits: • Monday, October 14, 2pm, Palo Alto, CA // at Earthwise (600 EAST MEADOW DRIVE Palo Alto, CA 94304) // w/Jenny Scheinman and co. // Reservations HERE • Tuesday, October 15, 7pm, San Francisco CA // Jazz at the Make-Out: Alexander Hawkins (UK), Low Bleeds (3225 22nd Street, SF, CA) // No Cover/Donations Accepted • Thursday, October 17, 8pm, Berkeley, CA // Alexander Hawkins Quartet, Bruce Ackley Solo at Tom's Place (3111 Deakin Street, Berkeley, CA) // Donations Accepted The band features Lisa Mezacappa, Jordan Glenn (Fred Frith Trio; 10/14 and 10/15 only), and Donald Robinson (10/17). We'll be tackling some a handful of old standbys, including music from our recent record with Tatsu Aoki and Michael Zerang: https://sluchaj.bandcamp.com/album/what-else-is-there

-

To be fair, I think that Jackie's experiments with free tempo music were earnest and purposeful. I just think that there was disconnect between how he understood things like harmony and forward motion and how the more naturalistic free players dealt with those concepts. My sense is that there were plenty of players who understood free music on some level but did not play it - e.g., openminded people like Gerald Wilson. Then there were players who could play in more open idioms, but whose approaches were somewhat incompatible with pure free playing - e.g., McLean, Dennis Charles, Bill Barron, etc. Then there were guys who were capable free players but probably didn't want anything to do with the music in a longterm sense - e.g., Rahsaan, Art Taylor, and so on.

-

Whoa - my initial post was from 17 years ago. Mercifully, all of this stuff is now readily available. The landscape for digital media completely changed in the interim between then and now.

_forumlogo.png.a607ef20a6e0c299ab2aa6443aa1f32e.png)