-

Posts

13,205 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Donations

0.00 USD

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Blogs

Everything posted by Larry Kart

-

Another fine recording of “Sonatas and Interludes” (with some comments on the work): https://louisgoldstein1.wordpress.com/about/

-

Maro's violinist sister Anahid Ajemian was the wife of George Avakian.

-

When you think about it -- and this has been the case with more than a few prizes over the years (I can cite some examples, though it might or might not be a first for the Nobel) -- Dylan more or less gave TO the Nobel the pre-existing "prize" of himself. That is, the Nobel people decided that it was in need of the cachet of someone such as Dylan.

-

I wasn't involved or particularly interested in that part of the discussion.

-

My point is simply that the accentuation Lennon chose for that phrase was not "any damn kind of an accentuation" but was meant to stick out/be (again, I hate this term) anthemic. That is, its rather lunging divergence from speech-like accentuation in general, whether or not that actual phrase would/could ever be spoken in any setting, is part and parcel of why it is what it is. No problem with that, but I think it is and aims to be unorthodox in effect. If it were not, I don't think the song would be the song it is.

-

'Larry, your premise seems to be linked to the notion that the words "strawberry fields forever" would be spoken in that order, together as a phrase, as a part of "normal speech", and...huh? Where does that happen?" Not exactly, but if one can imagine some sort of normal speech setup in which that phrase would occur -- e.g. "What sort of strange-looking reddish landscape is that?" "Strawberry fields forever." -- then the accents probably would not fall like this: "STRAW-berry "FI-elds for EV-er." I pretty much agree with "Point being just that 3 over 4 is a standard emphatic gambit," but I would excise "just" and perhaps "standard." The point that Lennon makes/is out to make with this gambit in this song is not only emphatic but also (and I swore I'd never use this term) anthemic. The phrase is meant to be something like a flashing (somewhat psychedelic?) neon sign. "Toto," it more or less says, "were not in Kansas anymore." Which is just fine -- that's the way the song needs to/has to be. Spector sure, but to me it seems to be a fair bit more unorthodox than Smokey's line.

-

with this evocatively titled Eddie Sauter piece:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xH4OdcW4pUAplayed here by Billy Butterfield’s Orch. from 1946? Just picked up a Hep CD by Butterfield’s orchestra and so far am very impressed by the band as whole (excellent reed section), by much of the writing, and by Billy too, of course.

-

The accents in that line from "Tracks of My Tears" are certainly more dramatic/drawn out than they would be in normal speech -- all to marvelous effect -- but I don't hear them falling in PLACES other than where they would in normal speech, as was the case in the songs/recordings I mentioned. Actually that line in "Tracks of My Tears" reminds me a bit of "There'll be no one unless that someone is you/I intend to be independently blue" from "Love Me or Leave Me." Or "I've got a house, a showplace/Still I can't get no place with you" from "I Can't Get Started." In both those cases, the framework is that of normal speech, but the lyric makes room for some doubling back rhythmic/sound-alike byplay: ""intend to be/independently"; "showplace"/"no place" within the overall rhythm scheme -- a la "my makeup"/"my break up." IMO, the genius of "Tears" is the placement of the words "I wear since."

-

Revisiting (more or less) jazz c. 1995-2016

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Miscellaneous Music

My Bostic experience is somewhat limited -- I know the Bostic hits that almost everyone knows because they were so much in the air for many years, but the only Bostic album I have is "The Complete Quintet Recordings" with Groove Holmes, Joe Pass, et al., which I like a lot, though I probably couldn't handle it as a steady diet. My remark was a way of saying that in the face of Carter's IMO garish freak show one might need/want to hear player like Bostic, who genuinely, as you say, has "the impact of being run over by a concrete mixer." -

I didn't say that speech-like word setting (which that line from "Tracks of My Tears" is a lovely example of) disappeared from pop music after the "Standards" era began to wither away/dry up/what have you, just that non- or less speech-like word setting became more common because a lot of pop music had other fish to fry.

-

Could have added the Vanguard date. To me, that and "Saxophone Colossus" and "Way Out West" are close to all of a piece. What richness, power, and wisdom! At that point, for me and some of my friends, Rollins was the most important living human being. In that vein, and FWIW, several months ago I was reading a nice coffee table book about the painter Alex Katz, and in it Katz mentioned that listening obsessively to "Way Out West" at the time it came out had a huge effect on his thinking, his painting, his whole orientation toward the world. IIRC, Katz mentioned not only the sheer glory of the music but also how it took off from tunes like "I'm an Old Cowhand" and "Wagon Wheels."

-

One of mine would be either Rollins' "Saxophone Colossus" or "Way Out West" Then either the Art Ensemble's "Congliptious," or "Old/Quartet," or Lester Bowie's "Number 1&2," or Roscoe Mitchell's "Sound" The Art Pepper Quartet (Tampa) Maybe "Jazz Giants '56" (with Roy Eldridge, Lester Young, Vic Dickinson, Teddy Wilson, Gene Ramey, and Jo Jones) Either "Bird DC 1952" or the Uptown Bird in Boston album with Dick Twardzik and Mingus I'm restricting myself to the LP era and later. Albums that compile 78s for me are a different animal. Individual 78s, even though I first encountered them on LPs -- that would be another list altogether.

-

Another voice heard from (with some bearing on Scott's point) from my book: STANDARDS AND ‘STANDARDS’ [1985] The greatest gap in American popular music may be the one that divides rock ‘n’ roll from the so-called “standard” tradition of songwriting and singing--the tunes of George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, and Cole Porter and the vocal styles of Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Judy Garland, and Fred Astaire (to name just a few of the major figures). Arising after World War I, and artistically and commercially vigorous until the end of World War II and a bit beyond, this was the music that several generations of Americans grew up on. And as the “standard” tag suggests, it was a music that seemed likely to remain in the forefront for some time. But rock ‘n’ roll changed all that, with the crucial dates probably being 1956 (when Elvis Presley's “Don't Be Cruel”/”Hound Dog” single climbed to the top of the pop, country, and rhythm-and-blues charts) and 1964 (when any doubts about the staying power of rock were erased by the advent of the Beatles). Rock in its various forms is undeniably the popular music of our time, while the standard tradition is close to being a museum piece--a development that many find regrettable but one that certainly can't be denied. Obvious, too, although time has healed some of the wounds, is the fundamental opposition between rock and the music that came before it. In fact, rock can be seen as a reaction to and a rejection of almost everything that the standard tradition represents--an attitude that a knowledgeable rock-devotee summed up when she referred to the music of Gershwin, Porter, and the rest as “all those songs about women getting in and out of taxicabs.” It was merely a sly dig in the ribs on her part, and at the time it made me laugh. But that remark has lingered in my mind; and the more I think about it, the more it seems to mean. For one thing, that remark had a point to it only because its perpetrator and I both knew that the songs of the standard tradition are supposed to be “sophisticated”-- a body of music about people who live in big cities, have a fair amount of cash, and work out their bittersweet romantic problems with a certain world-weary flair. But all that, my friend implied, is a crock--a set of attitudes that had nothing to do with the way she and most of the people she knew lived their lives, and that probably had little to do with the way most people lived their lives at the time those songs were written. And if there ever was a group of women who kept “getting in and out of taxicabs,” my friend’s first impulse would be to give them a swift kick in the shins. What that boils down to, I think, is a belief that when most standard-tradition songs are measured against the way things happen in real life, they turn out to be false. And by the same token, a good many rock fans and rock musicians seem to believe that their music is good not only because of its visceral kick but also because it is somehow more genuine--more realistic and natural--than the music that came before it. Now there is something to be said for that way of looking at things. Place a typical Cole Porter or Lorenz Hart lyric alongside something from Bruce Springsteen or Bob Dylan, and most people would say that “Born in the U.S.A.” and “It's Alright, Ma” are less artificial than “I Get a Kick Out of You” or “There's a Small Hotel.” But such a judgement probably would rest on the verbal content of songs, on the kinds of stories they try to tell--which is far from the only way to measure the realism and naturalness of a song. Consider, for instance, one of the most basic questions that arises in the mind of every singer and songwriter: How do I make the words and music fit together? One way to do this, and the way that became the norm during the standard era, was to come up with a melody and a rhythmic scheme that allowed the words of the song to emerge as conversationally as possible--in the patterns of everyday, person-to-person speech. (This was, of course, a practical necessity as well as a stylistic choice, because so many standard-era songs were written for the musical stage and had to flow easily out of spoken dialogue.) So if one simply speaks the lyric of any good standard song (say, Porter's “What Is This Thing Called Love?”) while trying to forget the melody and the rhythms that go along with it, there are two likely outcomes. First, the lyric can be spoken in a conversational tone of voice. And second, the words one would emphasize in normal speech are the same words that are emphasized when the song is sung. Natural, no? And while one wouldn't claim that this is true of every Cole Porter lyric, the story of “What Is This Thing Called Love?” doesn't seem very artificial either--measured against the world of 1930 (the year the song was written) or the world of today. But when songs of the rock era are looked at in this way, one comes up with some unexpected results. Not only do the lyrics tend to be more “poetic” than speechlike, they often don’t fit the music that goes along with them--that is, the words that would be emphasized if the lyrics were spoken are not the words that are emphasized when the songs are sung. For instance, in Dylan's “It's Alright, Ma,” the word “return” is sung by Dylan as “RE-turn,” while in Springsteen's “Backstreets” “became” is sung as “BE-came”--choices of emphasis that the rhythms of those songs demand but ones that run counter to the normal rhythms of speech. If you think that these are off-the-wall examples, look at the lyric sheet of your favorite rock album--first trying to speak the words in a conversational tone of voice and then listening to how they are sung. Quite often there will be a vast difference between the words you emphasized and the words the singer did. And when was the last time you heard anybody say anything the way the Beatles sing the title phrase of “Strawberry Fields Forever”? So what is going on here? While a cranky Rodgers and Hart fan might say that lack of craft is all that is involved, that's not quite the case, despite the amateurishness of much rock--if only because the same devices crop up in the work of such undeniably slick songwriters as Burt Bacharach and Barry Manilow. No, the problem is that we're stuck with two different notions of naturalness--one that takes off from human behavior as we commonly experience it and one that believes there is a deeper, “truer” nature that is at odds with the patterns of everyday life. Follow the first path and you have songs that stick close to the texture of normal speech and singers who interpret them that way. (One of Frank Sinatra's chief virtues is his ability to make almost any lyric sound intimate and conversational.) But when the second path is followed, you have songs and singers who not only feel free to shout, mutter, swoon, and groan but also tend to twist words this way and that to fit a pre-existing rhythm or melodic design. (On “Strawberry Fields Forever,” for instance, the non-speech-like word emphases of the title phrase arise because at that point composer John Lennon was interested in superimposing a patch of six-eight rhythm on the song’s prevailing four-four beat.) As a child of the “standards” era, I have my preferences. But I also know that this is not a matter of right or wrong. In fact, a glance at the history of music suggests that the kind of “natural” wordsetting that prevailed during the era of the standard song is less common than one might think. Seemingly built into the very idea of music is the belief that it is a language in itself, a sensuously ecstatic flow of meaning whose power to move us far exceeds that of common speech, and that it also does so in a deeper, more “poetic” way. Music’s desire to overide the patterns of discernable speech has been constrained at times (once, in the sixteenth century, by the Roman Catholic church, which decreed at the Council of Trent that the liturgical use of polyphonic music was permitted only if the texts of such pieces were not obscured), but that desire has never been suppressed, for in the long run both composers and listeners will resist. So perhaps no one should be surprised that we no longer live in an era when our pop songs were a kind of heightened conversation. What is surprising, perhaps, is that any of us grew up in a world where words and music were close to one thing.

-

Revisiting (more or less) jazz c. 1995-2016

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Miscellaneous Music

Early returns: Roy Hargrove's "Earfood": Never cared for him before but thought this latter-day (2008) album with his working group of the time might show improvement. Not IMO. The nanny-goat tone and blurted-out, wandering-all-over-the-lot "hot" lines -- yeesh. The second-coming of Jesse Drakes or Joe Guy. David Sanchez's "Obsessions" and several other Sanchez albums from before and after that one: Sanchez I don't get at all. Nothing awful but also nothing more personal and interesting than what one might have heard from a freshman in a Berklee practice room. James Carter Organ Trio "Out of Nowhere': Where's Earl Bostic when we need him? I pretty much can't believe this. Ravi Coltrane's "In Flux" and "Spirit Fiction": Sounds almost nothing like his father, has a genuine throaty soulfulness to his sound that IMO can't be bought or faked. How much he has/will have beyond that, I don't know, but so far I'm moved and on board. Seamus Blake's "The Call," "Stranger Things Have Happened," "The Bloomdaddies," and "Bellwether": Blake I knew of some already and kind of liked, but this was a heavy dose. Haven't pored over all of them, but his duet with Chris Cheek on "Sing Sing Sing" from "The Bloomdaddies" really cracked me up -- some crazy/serious fun. Stefon Harris' "Blackout Evolution" and "Urban Us' -- Have enjoyed several previous Harris albums, but these are much too "processed," especially sound-wise, for me; everything seems to be enclosed in Saran Wrap with all the air sucked out. Miguel Zenon's "Jibara" and "Awake": Hell, yes. And his rhythm sections! More Lovano albums than I care to list, including both "Trio Fascination" discs and "Saxophone Summit" with Brecker and Liebman: Over time I've been pretty much been worn down by Lovano's samey-ness and his somewhat "inhaled" tone, but I was pleasantly surprised by how alert and brainy he can be when taken all at once in mass quantities and how brainy Brecker and Liebman (neither among my favorites) sounded alongside him. Also, the "Summit" rhythm section (Phil Markowitz, Cecil McBee, and Billy Hart) is quite fine, and the varied trios of the second "Fascination" album are all at least interesting. The Blue Note All Stars' (Tim Hagans, Greg Osby, Javon Jackson, Kevin Hays, Essiet Esssiet, Bill Stewart) "Blue Spirit," from way back in 1996: Exceptionally intense and vigorous so far, really together, not just another semi-"Young Lions" jam session. A Bob Belden production. Hagans' "Twist and Out" (based on "Twist and Shout," natch) is a seriously hilarous/ hilariously serious line. Kris Davis' "The Slightest Shift" (2005): A new name to me, pianist-composer Davis is very impressive/thoughtful even meditative, reminiscent perhaps of Angela Sanchez. Sanchez's spouse of the time Tony Malaby is in fine appropriately rather reserved form. More to come, unless someone wants to cast a veto. -

Someone has been contributing to a local library sale an ever-growing batch of jazz CDs from 1995-2016, all them $2 each, all from players I know of but haven't in most cases been listening to that thoroughly or even at all during that period, e.g. Lovano, David Sanchez, Stefon Harris, Kenny Garrett, Roy Hargrove, Michael Zenon, Terence Blanchard, Ravi Coltrane, Seamus Blake, Dave Douglas, Jeff Watts, Sam Yahel, etc. So I've been buying almost everything they've put out at the sale -- in the name of "education" or "re-education," doncha know -- been listening my way through it all, and thought I might report after a while on how what I've heard strikes me. Some prior reactions/prejudices have been confirmed, others have been pleasantly altered, some players I knew of glancingly have come into focus. Perhaps I should add that this aforementioned "gap" in my jazz knowledge stems from the fact that during those years, and for some time before that, I was no longer a jazz journalist, had to buy all the CDs I acquired, and thus acquired only those that I felt fairly sure, for one reason or another, that I would like/were necessary. So beware -- unless I change my mind, the deluge is coming,

-

Recommending Texts for a course on the History of Jazz

Larry Kart replied to Face of the Bass's topic in Recommendations

Probably you jumped in at the right time. I myself bought a good number of remaindered copies at one time at a very decent price per book so I could have some to give away to people when I felt like it -- as I did fairly often; I have only four left. Those you'll have to pry from my dead hand. -

What Classical Music Are You Listening To?

Larry Kart replied to StarThrower's topic in Classical Discussion

Aymes' Frescobaldi is excellent IIRC. -

Plummer, post-George Russell, got better and better until he had to stop playing because off dental problems. He's excellent on this one: https://www.amazon.com/Detroit-Opium-Paul-Plummer-Enyard/dp/B007TNE980/ref=sr_1_5?s=music&ie=UTF8&qid=1476114157&sr=1-5&keywords=ron+enyard And there at least two more later on with him under Enyard's name. Plummer and his wife willed $1.9 milliion to the Indiana University jazz program: http://newsinfo.iu.edu/news-archive/21932.html

-

Got that one and a few others by Trimble, Good composer, had his own thing. Interview with him: http://www.bruceduffie.com/trimble.html

-

Recommending Texts for a course on the History of Jazz

Larry Kart replied to Face of the Bass's topic in Recommendations

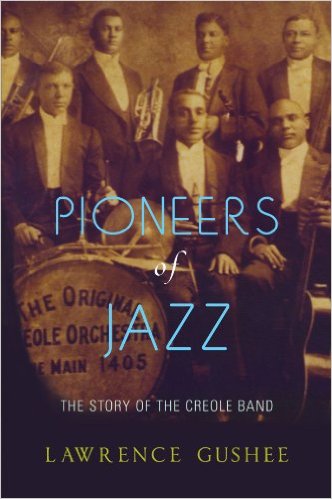

Sorry -- I didn't understand. In that case, this one is close to a must, a remarkable, enlightening, and highly readable piece of scholarship: https://www.amazon.com/Pioneers-Jazz-Story-Creole-Band/dp/0199732337/ref=sr_1_3?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1475977837&sr=1-3&keywords=lawrence+Gushee -

Recommending Texts for a course on the History of Jazz

Larry Kart replied to Face of the Bass's topic in Recommendations

May I suggest: https://www.amazon.com/Jazz-Search-Itself-Larry-Kart/dp/0300104200/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1475886084&sr=1-1&keywords=larry+kart I know the author, and he's a very nice guy. Also, though it's pricey even used on Amazon, I'm pretty sure that it can be found elsewhere "remaindered" fairly cheaply. Well, I've scouted around and it seems to be expensive everywhere. Hey -- I wrote a rare book! -

If I understand what Allen is saying, I think I agree with it. As long as I am who I am and as long as I find jazz interesting and important and I can find other people who want to listen to/talk about the music, and as long as the people who make and record the music can make enough of a living to keep doing what they're doing, any and all talk about jazz being cool or no longer being cool and/or how to make it cool again, etc. is nonsensical and pointless. Also, in the event that it should somehow become "cool" again, for better or for worse, I don't think that anything we say or do will be the cause of it.

-

One of the Klang albums has a piece dedicated to me, "Alone at the Brain," because James used to see me seated at a table by myself at the Hungry Brain, listening to the music:

-

"One can get hooked" is what I was thinking. The upfront presence of all the percussionists on the album makes me feel like my DNA is being rearranged.

-

You betcha. Backed by Jorge Maldonado and Eddie Rosado, Lead vocalist Hector "Papote" Jimenez is scorching. Jimenez in action: Colon, BTW, was the pianist for celebrated vocalist Hector Lavoe for many years. More Jimenez:

_forumlogo.png.a607ef20a6e0c299ab2aa6443aa1f32e.png)