-

Posts

13,205 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Donations

0.00 USD

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Blogs

Everything posted by Larry Kart

-

Not too harsh at all. Honest and soulful, I thought. A bit repetitious, though.

-

Nicely played

-

I think it was first Hawes trio album that was recorded at the Police Academy. IIRC the Cy Touff Pacific Jazz album was recorded there too. Good sound in that auditorium.

-

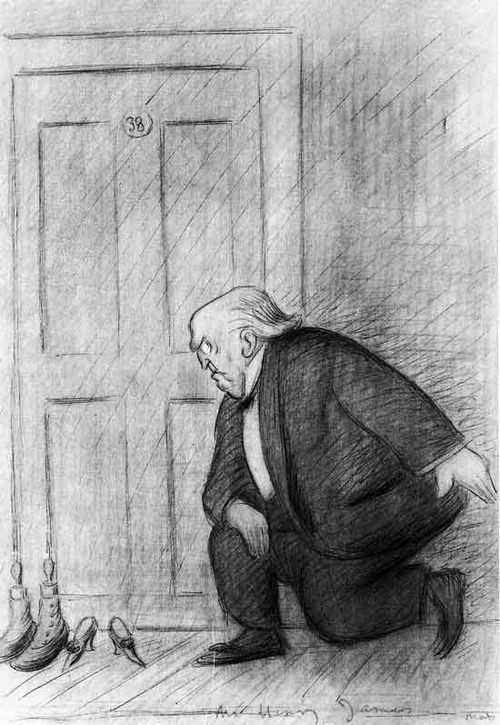

Leeway -- I think you may have put your finger on it. Denying Mrs. Proudie the right, or what have you, to have her last moments be "her own" is Trollope's IMO utterly just and necessary (necessary in both moral and fictional terms) verdict upon her. A few pages before, we are given what passes through Mrs. Proudie's mind shortly before her heart attack, this after her husband finally rises up on his hind legs after her most recent and most egregious attempt to usurp his prerogatives and says to her, "I am going to depart from here... I will not stay here to be the mark of scorn for all men's fingers. I will resign the diocese.' "You cannot do that," said his wife. "I can try at any rate,"said he.... Mrs. Proudie ... addressed her husband again. "What do you mean to say to Mr. Thumble when you see him?" "That is nothing to you." ..."Tom ... is that the way in which you speak to your wife?" "Yes it is. You have driven me to it. Why have you taken upon yourself to send that man to Hogglestock?" "Because it was right to do so. I came to you for instructions, and you would give me none." "I should have given you what instructions I pleased in proper time. Mr. Thumble shall not go to Hofgglestock next Sunday." "Who shall go then?" "Never mind, nobody. It does not matter to you. If you will leave me now I shall be obliged to you. There will be an end of all this very soon, -- very soon." Mrs. Proudie after this stood for a while thinking what she would say,: but she left the room without uttering another word. As she looked at him a hundred different thoughts came into her mind. She had loved him dearly, and she loved him still; but she knew now, --- at this moment felt absolutely sure -- that by him she was hated! In spite of all her roughness and temper, Mrs. Proudie was in this like other women, -- that she would fain have been loved had it been possible.... At the bottom of her heart she knew she had ben a bad wife. And yet she had meant to be a pattern wife! She had meant to be a good Christian, but she had so exercised her Christianity that not a soul in the world loved her, or would endure her presence if it could be avoided! She had sufficient insight to the minds and feelings of those sround her to be aware of this. And now her husband had told her that her tyranny to him was so overbearing that he must throw up his great position, and retire to an obscurity that would be exceptionally disgraceful to them both, which her conduct brought upon him in his high place before the world! Her heart was too full for speech; and she left him, very quietly closing the door behind her." A dead woman walking, I think. As Trollope says/shows quite tellingly IMO, she's dead because now he finally knows (at "the bottom of her heart," doncha know) that she is hateful and that "not a soul in the world loved her, or would endure her presence if it could be avoided!" As her husband says: "There will be an end of all this very soon, -- very soon." Further, I would say that what he says shortly before this is perhaps what really kills her: "That is nothing to you.... It does not matter to you." No more dire words could be spoken to such a being as Mrs. Proudie. And before that we have this crucial foreshadowing: "You have brought upon me such disgrace that I cannot hold up my head, You have ruined me. I wish I were dead; and it is all through you that I am driven to wish it." ... "Bishop," she said, the words that you speak are very sinful, very sinful." "You have made them sinful," he said.... "All I want of you is that you should arouse yourself and do your work." "I could do my work very well," he said, "if you were not here." "I suppose, then you wish I were dead?" said Mrs. Proudie. Again what more do you want? That Mrs. Proudie should be drawn and quartered while she tells us how that process feels? Here, as so often in Trollope, his relative decorum if you will, tells all we need to know and with a power that arguably exceeeds that of many more explicit ways of telling. In that respect, I think of Henry James' nagging at Trollope along these lines, when IMO Trollope's ability to delves quite deeply into virtually any form of human emotional and, for that matter, sexual behavior far exceeded that of the often prissy Mr. James. I think of Max Beerbohm's famous caricature of James (see below) in a hotel hallway, looking down with mingled horror and dismay upon two pairs of shoes -- one a man's, the other a woman's -- that have been placed outside the door for a servant to polish by morning. Clearly an assignation is taking place, and James not only disapproves but also, so it would seem, cannot really contemplate the physical reality of what acts are being engaged in on the other side of that door. Trollope -- the man and the novelist -- would have no trouble doing so.

-

"Two minutes after that she [Mrs. Proudie's maid, Mrs. Draper] returned, running into the room with her arms extended, and exclaiming, 'Oh, heavens, sir; mistress is dead!' Mr. Thumble, hardly knowing what he was about, followed the woman into the bedroom, and there he found himself standing awestruck before the corpse of her who had so lately been the presiding spirit of the palace. "The body was still resting on its legs, leaning against the end of the bed, while one of the arms was close clasped around the bed-post. The mouth was rigidly closed, but the eyes were open as though staring at him. Nevertheless there could be no doubt from the first glance that the woman was dead. He went up close to it, but did not dare to touch it." For me, the horror of the above, though in one sense the strokes are subtly made, is very intense. Trollope's point, or one of them here, is to palce the now utter final deadness of Mrs. Proudie against the fact that she "had so lately been the presiding spirit of the palace." Thus we get "the corpse of her" -- far more harsh in its emphasis on the "thingness" of the dead Mrs. Proudie, I think, than "her corpse," let alone "the corpse" or "her body," would have been. Then there's the macabre "[t]he body was still resting on its legs" and what follows in that sentence -- a being, or rather a non-being, who betrays several of the signs of life (still standing, still grasping something, eyes open) but "there could be no doubt from the first glance that the woman was dead." Then, finally and most awfully, the remaining two references to Mrs. Proudie in that paragraph are not even to "the corpse of her" but to "it." What more do you want? A coup de grace administered by Torquemada, Gilles de Retz, and the Marquis de Sade?

-

In his "Autobiography," Trollope says that while seated in his London club he overheard two clergyman complaining that Trollope's novels reintroduced the same characters too often and singled out Mrs. Proudie in particular. Then and there, says Trollope, I resolved to kill her off "before the week was over," and he did so. As for her death taking place offstage and therefore being anti-climactic, I'd have to reread to be sure, but I recall feeling that the way we're told what happens is just perfect, has a far greater impact for its being related at a certain objective distance and/or at one remove than it would have had if we experienced it close-up and in real time. In effect, the narration of her death more or less reproduces the transformation of this living fearsome human monster into the corpse of a fearsome human monster, which in effect is the issue -- that is, before her sudden death actually takes place, Mrs. Proudie has so much power in every respect within Trollope's fictional framework that even when opposed or oppressed she still seems indefatigable. In particular, at this late juncture, it's as though the force that drives her soul doesn't know and can never acknowledge the fact of her likely defeat. Thus, she must be STRUCK dead, as though by a blow from Heaven. And Trollope's omniscient narrator strategy there seems to me to have that effect.

-

Mea culpa -- while trying to delete a new post of my own, I mistakenly pushed the wrong delete button and deleted the whole darn thread. IIRC, there's no way to get a thread back once that is done.

-

I'd have to check. To be honest, the only track I listen usually is "Move It."

-

Raney's solo on "Move It" from "Two Jims and Zoot" is one of my favorite solos on any instrument (Raney follows Zoot). His playing in the subsequent two-guitar passage is also lovely. Kudos to Steve Swallow, too -- he really makes "Move It" move. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpBMOA_7F4U&list=PL0eFEn_kgjkDo4_DbIzWsNO5n1v3wNwa3&index=7

-

Read David Fallows' chapter on the Vespers in "Choral Music on Record" and you'll wonder whether any textually reliable, musically coherent recording of the work ever could be made. The unresolved and probably forever unresolvable issues involved are horrendous, but performers keep guessing, usually while pretending they are not: https://books.google.com/books?id=wKDT9lZ3jfkC&pg=PA1&dq=monteverdi+vespers+fallows&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiqrPiv08TMAhVIViYKHfnLDlsQ6AEILzAD#v=onepage&q=monteverdi%20vespers%20fallows&f=false

-

Nope -- just Keilberth and Kempe, though I've heard very good things about Konya and also heard that Rita Gorr's voice was shot by that time.

-

Picked up for $1 the other day a vintage 5-LP set of this 1953 live London recording from Bayreuth: Conductor Joseph Keilberth König Heinrich Josef Greindl Lohengrin Wolfgang Windgassen Elsa Eleanor Steber Telramund Hermann Uhde Ortrud Astrid Varnay Der Heerrufer Hans Braun Ein Edle Gerhard Stolze Ein Edle Josef Janko Ein Edle Alfons Herwig Ein Edle Theo Adam Chor und Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele Recorded July/August, 1953 Put it on to check it out and was just transfixed -- by the opera (the plot and the music; is there some forecasting of "Parsifal" here in both the latter and former?), the performance (everyone so far is good to great, especially the terrifying Varnay, the angelic Steber, the tormented Uhde, and the William Pitz-led chorus; Windgassen is right there emotionally, though perhaps no one in the post-war era had all that the more or less crazy role calls for). I've had for years on LP the much vaunted EMI Kempe set, which I haven't listened to in a long time and which never gripped me as this recording has. Perhaps because we're there at Bayreuth (this was Weiland Wagner's first production there), this seems less like a performance than a series of direct urgent human (plus a swan) confrontations. Part of the pleasure BTW comes from those 10 shortish LP sides. You take in a chunk that somehow seems just right, then you get up and put on the next one. Right -- Lohengrin is Parsifal's son, but I was also thinking of the frequently diaphanous music.

-

A comment on Craft's "Vespers" that rings true to me: "Craft's projection of the rhythms of this piece is not to be believed. No better or moresensitive or understanding musician has ever performed the Vespers thanCraft. He's a strong controlling presence. Unfortunately, his tenor soloists are not exactly virtuosos, and thatis only the most egregious evidence that this is not the most polishedpossible professional performance. (All of Craft's Columbia recordingswere done on a shoestring.)"

-

Agree with Moms on Gardiner and Parrott, though I've held onto the latter, but the one I keep returning to (Moms will scream) is the old Robert Craft: http://www.amazon.com/Monteverdi-Vespers-Blessed-Cantata-Trauerode/dp/B0000029SH/ref=sr_1_1?s=music&ie=UTF8&qid=1462481969&sr=1-1&keywords=craft+monteverdi

-

As I said this morning on the "What are you listening to now" thread, "I love/loved Doug's playing from the moment I first heard it on the ... album, "Introducing Doug Raney." Is there another case of an offspring whose playing at once stems so directly from his parent's yet is as individual and beautiful as Doug Raney's was? His duo albums with his father are sublime. Again, there's the shared stream of inspiration, yet it's easy to tell Jimmy and Doug apart.

-

Buddy Colette and his West Coast Friends

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Recommendations

Yes, indeed. -

Had a very nice encounter with Mal Waldron when he was on a rare visit to the U.S., backing up Sonny Stitt at the Jazz Medium in Chicago in the late '70s, IIRC. I told him how tickled I was by his intense, motivically oriented comping for Stitt, who clearly responded to what Mal was doing with big ears. Mal was pleased that someone had noticed and pleased as well that anyone Stateside still remembered who he was. Had a very nice encounter with Dexter Gordon too, but as enjoyable as it was (may have mentioned it here before), it was clear that Dexter's reason for our long interesting-to-me shmooze was in part that my presence in his Chicago hotel suite allowed him to fend off Maxine Gregg, who was mad as hell at him about his failure to start getting ready as soon as she wanted him to for some evening social affair (they were in town to promote the film "'Round Midnight"). Had a brief semi-nasty brush with Miles at the Plugged Nickel in 1969 (have written about it here before), but something good came of it -- an interview with Wayne Shorter that was not going to take place (he said that he had nothing to say) until Miles, from across the room, hoarsely said, "Don't tell him anything, Wayne" (Miles didn't know me but knew I worked for Dan Morgenstern at Down Beat). Wayne the contrarian pushed back at Miles and immediately told me he'd do the interview, which turned out quite well. Supposedly hadving nothing to say, Wayne the next day talked for about 90 minutes with such coherence that we ran the interview (which IIRC hardly needed editing) as a piece under Wayne's name and paid him about twice the normal DB freelance fee of the time for a piece of that length, maybe $400. About Ruby Braff, I think this Chicago Tribune piece (it's in my book) captures some aspects of him fairly well. The paragraph that begins "Show business," where he talks about the wisdom of calling up Sinatra and threatening him in order to get ahead, et al. makes it clear that Ruby's sense of himself as a character was at least in part wryly ironic, though I'm sure he could be wounding when he felt like it. RUBY BRAFF [1985] The most glorious anachronism in jazz, cornetist Ruby Braff really shouldn’t exist--for he may be the only man who has successfully stepped outside of the otherwise swift-running stream of jazz history, although Braff doesn’t quite see himself that way. But that is more than appropriate, because Braff has always been a one-of-a-kind guy whose gleefully combative attitude toward life recalls Groucho Marx’s famous quip that he “wouldn’t belong to any club that would have me as a member.” Suggest, for instance, that there is anything unlikely about what he has managed to do--build a truly individual style that nonetheless pays handsome tribute to the genius of Louis Armstrong--and the fifty-eight-year-old Braff bridles at the thought. “Hey,” he says, “I was playing in joints when I was still in grade school, and by the time bebop came along, in 1945 and ’46, I already was deeply into music. So there wasn’t anything odd about what I was doing. You know what they say, ‘You are what you eat,’ and I was just playing the way I heard people play.” But there is something unusual about Braff’s achievement. Even though he was, back then, not the only young player who felt himself to be more in tune with the music of Armstrong et al. than with the music of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, he was almost alone in his ability to steer clear of the tricky waters of re-creation and revivalism. Inspired by the past, Braff has always been a musician of the present, and his love of what might be called “the great jazz tradition” has only increased the individuality of his plush, throbbing tone and the gracefully soaring phrases with which, as one critic put it, Braff “adores the melody.” So at a time when the virtues of the great tradition are seldom to be found, Braff not only presents them with all of their original force but also puts them to very personal use--creating his own music with a passion that transcends the boundaries of style. Born in the Boston suburb of Roxbury, Mass., the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, Braff knew early on that he was destined to be “a performing animal.” “Were I not playing the horn,” he claims, “I’d be in vaudeville--a magician, a comic, something on the stage. And the reason I know that is that I know how I responded to performers, even when I was a baby. I’d hear something on the radio, even [boy tenor] Bobby Breen [here Braff does a choice takeoff on Breen singing “When My Dreamboat Comes Home”], and it would just stir things in me, drive me crazy. I, too, wanted to make noises like that and excite somebody the way those noises excited me.” The noisemaker Braff had his heart set on was a tenor saxophone, but when his parents took their rather diminutive son to a music store, they felt a trumpet would be more his size--a choice for which the jazz world has reason to be grateful. Switching from trumpet to cornet “because it looks better for shorter people” (Braff now stands five feet, four inches tall) and also because “it has a mellower sound,” Braff continued to think in saxophone terms --“which is good,” he explains, “because if you think of another instrument, you can’t help but sound a little different.” Braff found himself in good musical company early on--his compatriots included such older masters as clarinetist Edmond Hall, trombonist Vic Dickenson and drummer Sid Catlett--and by the time Braff made his first recording, under Dickenson’s leadership in 1953, he was a remarkably mature player. A number of fine Braff recordings were made in the wake of that striking debut, including several superb albums that paired him with pianist Ellis Larkins. But even though he was showered with praise by many critics, the course of Braff’s career was not destined to be smooth. For one thing, his chosen style was not fashionably hip, and Braff, quite rightly, had no desire to change the way he played. On the other hand,Braff was praised in some quarters because of his apparent lack of modernity, which had the unfortunate side-effect of typing him as an artist that only tradition-minded listeners were likely to enjoy. Combine that with Braff’s somewhat bristly manner, which probably stems from the fierce artistic demands he places on himself, and one has the makings of a man who was born to wear the label “underrated.” “All I know,” says Braff, “is that wherever I’ve played, people have liked what they heard. The problem was, nobody was getting to hear me enough.” And with that, Braff sets off one of his typical strings of verbal fireworks--a half-serious, half-joking series of remarks that he delivers in an obsessive rush and at such a high volume level that one hardly needs a telephone to hear him. Add an exclamation point to every phrase, and you’ll get some of the flavor. “I’m a drama freak,” Braff begins. “I like to dramatize a tune and I’m always trying to communicate, which is the difference between being a performer and a musician. There are many musicians, but they aren’t performers, they’re just instrumentalists who belong in an orchestra reading charts--which is all right, ain’t nothing wrong with that. But the trouble with this world is that most of these people are on the stand today, playing 700 choruses! “Loudness and softness and longness and shortness--if you’re a performing animal, you know about those things. I was brought up on the two-and-a-half-minute record, where you heard a marvelous composition and little solos, returns to a theme and highs and lows, which is what I think about when I’m playing, even though sometimes I play much longer than that. I’m thinking ‘stretch in,’ not ‘stretch out’--‘in, in, in!’ You see, I treat me as though I were a customer. When I’m playing I’m thinking, ‘What are you doing now? Okay, that’s enough of that,’ so the audience always knows what I’m talking about. I mean, a truck driver can listen to Johnny Hodges and know this is something that makes him feel good--an idiot can hear those magical tones and they’ll tug at his heartstrings! “Show business--I love show business. If I had my way, I’d be up there with dancers and magicians and lights and everything. Oh, why can’t I have magic, so that when I lift my horn up and want it to disappear, it vanishes out of my hand! That can be done with lights, I know it can! Oh, why can’t I be tremendous? If I were a star, I’d have such fun! Sinatra--why don’t I get the exposure he gets? Maybe I should call him up and threaten him. No, no, I’d better not do that--that is not the way to go. But why did they ruin everything? I mean, this is the worst world I’ve ever lived in. All I want to do is go over the rainbow, to someplace better than where I was. And why can’t I have my own talk show?” Sorting through this barrage of vintage Braff-isms, with its built-in wryness and its wild swings in mood, one simultaneously feels that almost none of it, and all of it, should be taken at face value. Braff really does want to be “tremendous” and all the rest. But even as he bursts at the seams with the need to impose his ego upon the whole world, he is self-aware enough to know that his gifts are best suited to the relatively intimate medium of the cornet. In fact, when Braff pours his turbulent soul through that horn, it seems that the sheer pressure of his drive to communicate to one and all is what makes his music so powerful in a nightclub setting--as though one were bearing witness to a beauty that could, at any moment, explode. “Ruby is a traditionalist,” says Braff’s longtime friend, Tony Bennett, “in the sense that he knows the roots and the treasures--Louis Armstrong, Judy Garland, Bix Beiderbecke and all the rest. But then, having learned from them, he takes that knowledge and flies with it in a very modern way. Like all great jazz musicians, Ruby is right in the ‘now,’ and when people get a chance to hear him, they’re always moved. I remember last year, I went to one of those really hardnosed ASCAP [American Society of Composers and Performers] meetings that the SongWriters Hall of Fame puts on. Every big composer was in the audience, and a whole bunch of artists performed, but it was more of a social occasion until Ruby came out to back a singer. He played a few solos and obbligatos, and suddenly it was like everyone was swooning. They didn’t know who Ruby was, and then when they heard this magnificent horn, they just went ‘Wow!’ But that’s what Ruby can do to you if he gets a chance.”

-

Buddy Colette and his West Coast Friends

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Recommendations

Nope, not full size but ample.Label owner/musician Johnny Otis designed the cover, maybe even created that sculpture, though I'm not sure about the latter. Don't know "Jazz Heat, Bongo Beat," but unlike you, I'm not into exotica, though I recall enjoying at least one of Les Baxter's hits in my youth. -

Buddy Colette and his West Coast Friends

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Recommendations

The "Tanganyika" cover is reproduced in the booklet. -

Listening tonight to this compilation of two 1956 small-group dates with similar personnel -- Colette's "Tanganyika" and drummer Max Albright's "Mood for Max" -- I was especially taken with the work of trumpeter John Anderson (1921-74). A suave graceful modernist with a warm big tone and impressive chops, he might be described as residing somewhere between Joe Wilder and Ray Copeland, which is a nice place to be. One assumes that his original inspirations were Harry Edison and Fats Navarro, though there are a few Gillispie-ish touches. In any case, Anderson was his own man and a very impressive player. Anyone know whether he can be heard at length elsewhere? BTW, familiar though I am with Colette's work on his various horns, I was surprised by how much several of his alto solos here sound like Paul Desmond. A plus is the work of bassists Curtis Counce (on "Tanganyika") and Joe Comfort. Albright's drumming is a bit tiddly at times, but not enough to really matter. http://www.amazon.com/West-Coast-Friends-Buddy-Collette/dp/B001PQG0XE/ref=sr_1_3?s=music&ie=UTF8&qid=1462063424&sr=1-3&keywords=buddy+collette+west

-

-

Don't know that one myself. There's some tasty Cohn baritone on John Benson Brooks' "Folk Jazz U.S. A.," which also has some lovely Zoot on alto.

-

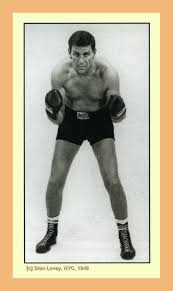

No, it was Stan Levey, not Getz, whom Stitt ratted on to the narcs and thus sent to prison and who then, after getting out, brought a hit man to Stitt's gig. I would have thought that "It Don't Mean a Thing (If it Ain't Got that Swing)" from "Diz And Getz" would have told Dizzy at least that there's no tempo that Getz can't make.

-

A post from vibist Charlie Shoemake on Doug Ramsey’s blog, about drummer Stan Levey: ‘About the recording [“For Musicians Only”] Stan told me that Dizzy and Sonny Stitt had planned to burn Stan Getz out with the incredible blazing tempos but he turned out to be too much for them and actually had THEM a bit on the defensive. He also told me that when they kicked off those tempos John Lewis folded his hands and just sat there for almost the entire session. ‘More trivia concerning Sonny Stitt. Conte Candoli told me that Stitt was the one that had given Stan up to the drug police in order to save himself, thus sending Stan to prison. When I asked Stan about it he said that it was true and that when he got out he took a notorious Philadelphia hit man that he knew from his boxing days to where Sonny Stitt was playing and they sat in the front row causing Sonny Stitt to turn ashen white. I said to Stan…"but all of those recordings you made with him years after that, what was that like?” Stan said they never spoke but every once in a while he would see Sonny glance over at him very nervously. He also said that going to prison actually saved his life because he got completely clean and married a beautiful girl, Angela, who was a wonderful person and a steady rock for him the rest of his life.’

-

What Classical Music Are You Listening To?

Larry Kart replied to StarThrower's topic in Classical Discussion

It ain't supposed to be.

_forumlogo.png.a607ef20a6e0c299ab2aa6443aa1f32e.png)