-

Posts

13,205 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Donations

0.00 USD

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Blogs

Everything posted by Larry Kart

-

No, but I have heard "Baritone Madness."

-

Thanks for the recommendation. The bass-drum team on "Tour de Force" -- Eddie Gomez and Bill Stewart -- is superb ... and normally I'm not a Gomez fan; he's brilliant here. Nick feeds on Stewart's characteristic looseness, if looseness is the right word,

-

Knew of him for years and had run across him as a sideman but recently bought my first Brignola leader date, his final one I believe -- "Tour De Force" (Reservoir). Wow. His agility, rich sound, and sense of swing were no surprise, but the sheer quality of his thinking was -- his lines would be terrific no matter what horn he played, although some of his ideas do seem baritone specific, which is as it should be. I've ordered three more Brignola CDs.

-

I once played golf with Nordine. Very nice guy but not a good golfer; neither was I. I'd just showed up that weekday morning at a local public course in Winnetka, Il., and he and I were paired together. Strange feeling for a while talking to a man whose distinctive voice had so many associations -- not only to "Word Jazz" but also to a good many Chicago-area radio commercials over the years.

-

Joel Siegel obit, just so it's clear which person of that name wrote about the Dearie debacle): Joel E. Siegel Dies By Louie Estrada March 13, 2004 Joel E. Siegel, 63, a retired Georgetown University English professor who also was a lyricist, music producer and freelance film and music critic for the Washington City Paper, died of spinal meningitis March 11 at George Washington University Hospital. Dr. Siegel mostly taught film studies at Georgetown, where he was a faculty member for 32 years, until 1998. He offered the college's earliest courses on film studies and built the curriculum while maintaining a vibrant career in the arts outside the classroom. He staged singer and songwriter series at the Kennedy Center, the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the University of Maryland; managed singers and produced their albums; and in 1973 authored "Val Lewton: The Reality of Terror," about the legendary film producer. In 1993, he shared a Grammy for best album notes with Buck Clayton and Phil Schaap for their book accompanying the 10-CD set "The Complete Billie Holiday on Verve, 1945-1959." He was perhaps most recognizable for his freelance music, book and film reviews that appeared in the Washington City Paper for the past 20 years. His last movie review, about the recent revival of Francis Ford Coppola's 1982 film "One From the Heart," appeared in January. He utilized an economical writing style with short, declarative sentences in his critiques, which sometimes related occurrences in his personal life, said Leonard Roberge, arts editor at the City Paper. In one review, Dr. Siegel likened the displeasure of watching a movie with a bad ending after enjoying two-thirds of the film to a dining experience he had at a restaurant. He wrote how fabulous the food tasted until the very last bite, when lifting his fork he found an insect plastered to the underside, ruining the entire meal. "He established a relationship with readers, confided in them," Roberge said. Dr. Siegel also wrote reviews for JazzTimes, Washingtonian magazine and the old Washington Newsworks and Washington Tribune newspapers. As a music producer, he managed Washington jazz singer-songwriter Shirley Horn in the 1980s and 1990s, after she had taken time off to raise her children. He produced her 1987 album "Softly" and co-produced her "You Won't Forget Me" and "I Love You, Paris" albums. He was an associate producer on her album "Here's to Life." In the early 1990s, he wrote English lyrics for the Italian song "Estate." Dr. Siegel also produced jazz vocalist Patti Wicks's recent album "Love Locked Out." He would often take sabbaticals from teaching to pursue his other interests or simply squeeze in projects between the courses he taught, said his sister, Judith Siegel-Baum. Among his favorite activities was penning lyrics. His long list of credits includes the songs "Noir," recorded by Claire Martin; "The Ways of Love," recorded by Shirley Horn and Wynton Marsalis; "I Watch You Sleep," recorded by Jackie Cain and Roy Kral; and the theme song of the 1979 war movie "Yanks." Dr. Siegel, an Arlington resident, was a native of Washington, Pa. He graduated from Cornell University and received a master's degree and a doctorate in English from Northwestern University. His doctoral dissertation was on film director Vincent Minnelli. In addition to his sister, of New York, survivors include his parents, Sherman H. and Miriam Danzinger Siegel of Washington, Pa.

-

A Blossom Dearie story from the late Joel Siegel, originally posted on the Songbirds site. (BTW I did survive doing an interview with Blossom): The Blossom Experience By Joel E. Siegel In the early '80s, I produced a concert series at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. called "Great American Songwriters." The idea was to match up first-class jazz and cabaret performers with GAS composers or, in rare cases, special themes. The series ran for three and a half years in a lovely 197-seat auditorium with a superb Steinway piano. Many of the programs were taped by and subsequently broadcast on National Public Radio. Overall, there were about 30 concerts spread over three years. Here's a sample of the programs: Jackie and Roy doing concerts of Stephen Sondheim, Alec Wilder and a collection of songs they introduced; Pinky Winters and Lou Levy doing Johnny Mandel; Carol Sloane doing Rodgers and Hart; Charles DeForest doing Harry Warren; Ethabelle doing Harold Arlen and John Latouche; Sheila Jordan doing songs by jazz musicians; Buddy Barnes doing Cole Porter; Shirley Horn doing Duke Ellington and Curtis Lewis' "The Garden of the Blues Suite"; Mark Murphy doing Dorothy Fields; Julie Wilson doing Arlen and Kurt Weill, Sandra King making her American debut with a Vernon Duke program. Well, you get the idea. Others in the series included Chris Connor, Margaret Whiting, Carol Fredette, Ronny Whyte, Rose Murphy, Dardanelle, Bob Dorough, Dave Frishberg and many more. (Apologies to anyone I forgot to mention. My box of materials with the full list of performers is stored in my attic.) Obviously, this was a perfect venue for Our Blossom. My negotiations with her were rather complicated. From the outset, she rejected the idea of preparing a special program as all of the others did. ("I'm a Great American Songwriter myself," she informed me.) I decided to bend the rules because Blossom is special and I knew she would draw a full house. So I gave her carte blanche to do whatever she wanted. I told her that traditionally we had a celebration dinner at a restaurant in Chinatown after the 4 p.m. concerts, to which a handful of people associated with the series were invited-Jennifer, my helpful and charming young intern-assistant from the Corcoran, Mr. and Mrs. Blackwell, several patrons of the series, etc. Blossom told me that her brother Walter and his wife would be coming from Winchester, Virginia, and asked that they be invited to dinner and that a driver be assigned to them. The Blackwells graciously volunteered provide them with transportation. On Saturday, I picked Blossom up at Union Station and drove her to her hotel, a comfortable place just across the bridge from Georgetown. She was tired so I left her to rest after checking her in. The next morning, I was awakened at 8 a.m. by a call from her. She said that she needed to rehearse and had to find a place with a piano. This struck me as rather odd since she was performing solo and doing songs she had performed hundreds, probably thousands of times before-"I'm Shadowing You", "My New Celebrity Is You" etc. I told her that I had a piano, albeit not a very good one, and would be happy to drive into D.C. from Arlington, Virginia, and bring her to my place. She said she needed to have breakfast first, and would call me as soon as she was finished. I couldn't fall back to sleep, so I awaited her call. 9 a.m. 10 a.m. 11 a.m. 12 p.m. No call. Finally, I began phoning her, but got no response. 1 p.m. 2 p.m. I'm getting nervous because we have a 3 p.m. sound check. Finally, she called me at 2:30. I told her that I was worried that something had happened to her. She sternly said, "I told you that I was going for breakfast." "But that was more than 6 hours ago," I pointed out. "Oh," she said, "They were very slow." End of explanation. I hurriedly picked her up and took her to the Corcoran. I had told her in advance that NPR was taping the shows and outlined the terms of their contract with the artists. When we arrived at the Gallery, she saw the sound truck, turned to me and imperiously said "It is not permitted." When I inquired WHAT was not permitted, she replied the taping of her show. This was the first time I had been informed of this stricture. An angry NPR sound crew, working overtime on Sunday, was turned away. We entered the auditorium where the obliging Jennifer was setting things up. Nothing this young woman did satisfied Blossom. The lights were too bright. The lights were too dim. The piano had to be moved numerous times. Instead of requesting changes politely, Blossom kept snapping at the flustered young women in the most insulting manner. Embarrassed by her behavior, I drew Blossom aside and quietly said "You know, you can catch more flies with honey than vinegar." She looked at me blankly and replied "I don't know what that means." Finally, we managed to set things up to Blossom's apparent satisfaction. Just before we were to open the doors, she walked out into the seating area, called me over and asked "Where are all the flowers?" Totally disgruntled by her, I replied "I didn't bring them, Blossom. Did you?" The audience enters-a packed house with standees-and I introduce Blossom. She takes elaborate bows, then notices a woman standing by the entrance door holding a baby. Blossom points to her and asks "Is that a baby?" The woman indicates that it is. "Does it cry?" Blossom inquires. The woman says "He's asleep. If he wakes up and cries, I'll take him outside. That's why I'm standing by the door." Blossom repeats her earlier mantra "It is not permitted" and the woman and her baby are banished. This behavior does not endear her to the audience. Blossom performs the first half of her program. Not one of her shining hours. She hits a number of keyboard clunkers. (Maybe she was right about needing to rehearse.) Just before the intermission, she spots Felix Grant, the famous Washington jazz disc jockey, in the audience. She comes to the front of the stage, introduces him and makes a little speech. "I have never performed in the nation's capital before, and for years Felix has been trying to arrange a concert for me here. I guess this must be a pretty big day for you, right Felix?" On that modest note, she retired to the dressing room. During the intermission, Shirley Horn, who was in the audience and had known Blossom since her New York debut with Miles Davis at the Village Vanguard, popped backstage to say hello. Shirley returned a few minutes later with a puzzled look on her face. I asked whether Blossom was acting strangely. Shirley nodded her head and said, metaphorically, "I think she's gone inside, locked the door and now she can't get out." The second set unfolded without incident, apart from a few pianistic clangers. Afterwards, Blossom briefly received her audience. Two gay men, who were regulars at the series, told her how much they enjoyed her, and made a point of saying that they had attended her PREVIOUS D.C. appearance at a gay-owned supper club called the Way Off Broadway, where Barbara Cook, Anita' O'Day. Helen Humes and others had also worked. (Blossom had revised history so that the venerable Corcoran, which she must have perceived as a more reputable venue, was now the site of her "official" Washington debut.) She pretended that she didn't know what they were referring to. Concert is over. Time for dinner. The Blackwells escort Blossom's brother and wife to the restaurant. We close the auditorium, and I start to drive Blossom to the same location. Only she doesn't want to go there. "I want to see the monuments," she insists. "But everyone's waiting for us," I reply. "I'm not hungry," she pouts. "I want to see the monuments." I give her an abbreviated tour of Tourist Washington and take her to Hunan Gourmet where everyone has grown restless waiting for her. Arriving at the large round table I reserved that seated 10 people, Blossom complained that she didn't like the chair that was left for her. She made everybody stand up and forced them to exchange seats to suit her. Then she announced to the starving gathering that she was not hungry. Helpfully, I suggested that we could just have drinks and snacks. "No snacks!" she commanded. We ordered drinks and, despite her instructions, some appetizers. Before the order arrived, she announced that she was leaving and asked if someone would hail her a cab. In a moment worthy of a Lubitsch comedy, every man at the table leapt up to escort her to the street and get rid of her. I can't recall whether or not her nice relatives remained with us, but I think they did. (Bill Blackwell probably can probably clarify this.) As soon as she was gone, we trashed her roundly before ravenously consuming a huge meal. Subsequently, I learned that Blossom had taken that cab to Charlie's, a jazz club in Georgetown, to see if she could secure a future gig. Had she bothered to inform us of her intention, we could have convened at Charlie's rather than in Chinatown. To this day, I have yet to solve the mystery of her six-hour breakfast. Another one from Bill Reed: 'One day Blossom Dearie came on business to the office of a former New York friend of mine. But all she could bring herself to talk about were the unsanitary conditions in his john: “The yoooo-rine [she pronounced it] stains” on the wall next to the toilet. Dearie then insisted that he send an aide to the deli downstairs to buy scouring powder and when it arrived, she set to work cleaning his toilet. She finished, then departed, and they never really did get around to discussing business. (And Marlene Dietrich thought that SHE was---as self-described---"The Queen of Ajax.") Eventually the insulted party with the dirty loo got even with Dearie by becoming her final (mis)manager.'

-

I think Rollins + Four was the first album I bought with money I had earned. Our record player was in the living room, where my Dad typically would sit down after dinner on the couch to read the newspaper, while I quite obsessively for a time played "Pent Up House" over and over -- fascinated by Brownie's solo, particularly the burbling grace-noted passage toward the end, with Max boiling underneath. Finally one night my Dad looked up from his paper and said, "Don't you have another record!"

-

Been enjoying the Archer Mayor police procedural series, set in Vermont, about Joe Gunther -- police chief in Brattleboro, later connected with the VBI (Vermont Bureau of Investigation). The Joe Gunther Series “Archer Mayor’s Vermont police procedurals are the best thing going…” —New York Times Book Review Archer Mayor’s Joe Gunther detective series, 26 books in all, is one of the most enduring and critically acclaimed police procedural series being written today. For years, Archer has integrated actual police methodology with intricately detailed plot lines into novels that The New York Timeshas called “dazzling,” and Booklist has said are “among the best cop stories being written today.” Whereas many writers base their books on only interviews and scholarly research, Mayor’s novels are based on actual experience in the field. The result adds a depth, detail and veracity to his characters and their tribulations that has led The New York Times to call him “the boss man on procedures,” and the Arizona Daily Star to write, “Few deliver such well-rounded novels of such consistent high quality.” The Joe Gunther detective series began in 1988 with Open Season, and now includes Borderlines, Scent of Evil, The Skeleton’s Knee, Fruits of the Poisonous Tree, The Dark Root, The Ragman’s Memory, Bellows Falls, The Disposable Man, Occam’s Razor, Marble Mask, Tucker Peak, The Sniper’s Wife, Gatekeeper, The Surrogate Thief, St. Albans Fire, The Second Mouse, Chat, The Catch, The Price of Malice, Red Herring, Tag Man, Paradise City, Three Can Keep A Secret and The Company She Kept. The Los Angeles Times featured Scent of Evil in its 1992 year-end list of recommend readings and proclaimed The Skeleton’s Knee “one of the best ten mystery books of the year” in 1993. That book also prompted The New York Times to call Mayor “one of the most sophisticated stylists in the genre,” and in 1997, to proclaim The Ragman’s Memory one of only eleven “Notable” mysteries of the year—an honor it repeated in 2002 with The Sniper’s Wife. Me again: I can vouch for "Bury the Lead," "The Catch," "The Ragman's Memory," and "Borderlines." The Joe Gunther Series 29. Bury the Lead (2018) 28. Trace (2017) 27. Presumption of Guilt (2016) 26. The Company She Kept (2015) 25. Proof Positive (2014) 24. Three Can Keep a Secret (2013) 23. Paradise City (2012) 22. Tag Man (2011) 21. Red Herring (2010) 20. The Price of Malice (2009) 19. The Catch (2008) 18. Chat (2007) 17. The Second Mouse (2006) 16. St. Albans Fire (2005) 15. The Surrogate Thief (2004) 14. Gatekeeper (2003) 13. The Sniper’s Wife (2002) 12. Tucker Peak (2001) 11. The Marble Mask (2000) 10. Occam’s Razor (1999) 9. The Disposable Man (1998) 8. Bellows Falls (1997) 7. The Ragman’s Memory (1996) 6. The Dark Root (1995) 5. Fruits of the Poisonous Tree (1994) 4. The Skeleton’s Knee (1993) 3. Scent of Evil (1992) 2. Borderlines (1990) 1. Open Season (1988)

-

"Solar," from Slide Hampton's "Roots" (Criss Cross, 1985), with Clifford Jordan, Cedar Walton, David Williams, and Billy Higgins. This may be the best Cedar Walton solo I've ever heard:

-

A big Lee Child fan here, but I disagree with Dave James' "completely and totally mindless." While Reacher's near implacable, highly honed physical skills are a key given, especially in that few of his antagonists are aware that they're facing in him not just another very big/muscular guy, every Reacher novel I recall turns not only (and not really that much) on his ability to be effectively violent but also (and I would say primarily) on his ability to think through/figure out what is always a very puzzling/"what the heck is going on here?" initial situation -- and things typically remain quite puzzling for a good while.. Without the "thinking" Reacher, the bashing Reacher would be up a creek. Further, the bashing Reacher is, I would say, quite thoughtful in his bashing. As is emphasized time and again, he knows exactly how to rapidly muster his immense physical skills to fit the given situation, (we're usually told just how he scopes things out along those lines), while his antagonists typically do not know how to effectively muster the force that's available to them. They're out-thought as much as they're out-fought.

-

I think that Webern disc I plugged might have been this one with the Vienna Philharmonic: https://www.amazon.com/Schoenburg-Survivor-Warsaw-Webern-Orchestral/dp/B000001GF3

-

"Schuller was considered the leading composer of serial composition in the US, but don't let that bother you.." Not "considered the leading composer of serial composition in the US" -- I think that would have been Milton Babbitt or, a bit later on, Charles Wuorinen -- but "a leading composer of serial composition in the US." [FWIW, Schuller's wholly serial (and rather naively rigid) Piano Concerto (1962) is as turgid as any serial work I know or could imagine -- albeit in the (sonically rather dim) recording of its premiere performance, it is not, as far as I can tell, at all well played by soloist or orchestra. https://www.amazon.com/Schuller-Three-Concertos-Piano-Bassoon/dp/B000005VYD/ref=sr_1_8?keywords=schuller+piano+concerto&qid=1549927670&s=music&sr=1-8-catcorr I say "naively rigid" because Schuller states that his goal was to write a piece in which "the disposition of all musical elements ... not only pitch but also dynamics, duration or rhythms, timbre, all internal relationships, and even the overall form of the work are directly determined by the series or tone row." Even Boulez tried to go that far only for a hot (or cold) minute, after which he backed off and stated that such "total serialism" was a canard. In any case, Schuller's considerable musical gifts were not of the sort that could do more, having adopted such strictures, than rattle around in the chains in which he'd draped himself.] Speaking only for myself BTW -- and this probably touches on what Jim Sangrey has said as well as on what sgcim has said -- I was introduced to the music of Schoenberg, Webern, Berg et al. when I was a junior in high school in the late '50s (a musician friend admired that music and played Schoenberg on the piano, and I acquired as many recordings as I could). You'll have to trust me on this but I found much of this music quite magical and also relatively lucid. Tthe first piece that blew me away was Berg's "Altenberg Leider in the Robert Craft recording with Bethany Beardslee; and as for the "techniques" being off-putting or incomprehensible, the relative (or even total) absence of triadic tonal harmonic functions -- these I had been familiar with for many years -- seemed quite ... "refreshing" isn't quite the right term, but it felt as though the music and I had entered a relatively new world in which new sorts of beauty were to be found. Not everything of that sort made sense to me or went down well -- like many, I had problems with Schoenberg's Wind Quintet, but I now think that's because the recorded performances available back then of that very difficult piece weren't at all up to snuff. I any case, from then until now, I don't think I've had a problem getting into any piece of serial of twelve-tone music because it was that sort of music; rather, I find it fairly easy to sort out the pieces that work for me from the pieces that don't -- ... but then my judgments there are always right -- and further, detect which performances are good or better and those that are not. BTW, as for knowing the compositional techniques/details inside out as being necessary to understanding and being moved by this music -- at one point Schoenberg's brother-in-law violinist Rudolf Kolisch, leader of the Kolisch Quartet, approached Schoenberg with a copy of the Schoenberg quartet they were preparing to premiere (it was the third). Kolisch had highlighted every tone row (as he saw it and to the best of his ability) and took the marked-up score to Schoenberg for comment on the accuracy of what Kolisch had done and hoping for his approval. Schoenberg responded in a letter from July 1932: "You have rightly worked out the series in my string quartet (apart from one detail...). You must have gone to a great deal of trouble, and I don't think I would have had the patience to do it. But do you think that one's any better for knowing it? I can't quite see it that way. My firm belief is that for a composer who doesn't quite yet know his way about with the use of series it may give some idea of how to set about it -- a purely technical indication of the possibility of getting something out of the series. But this isn't where the aesthetic qualities reveal themselves, or, if so, only incidentally. I can't utter too many warnings against over-rating these analyses, since after all they only lead to what I have always been dead against: seeing how it is done; whereasI have always helped people to see what is.... I can't say it often enough: may works are twelve-note compositions, not twelve-note compositions. "It goes without saying that I know and never forget that that even in making such investigations you never cease to live with what is actually the source of your relationship to this music: its spiritual, auditory musical substance...." (My emphasis)

-

But Schoenberg himself, especially later on, fairly often didn't "avoid" those "things to avoid," instead following his ear. Further, I agree with Chuck's "Too many great works were created in the system..." remark above. Further, those great works that were created in the system are quite individual.

-

Re: "Fine resisted the twelve tone technique." In that interview with Fine there's this exchange: "In these later years, then, you weren’t composing by avoidance, so to speak. "Fine: No." I don't think Fine avoided or "resisted," or had any need to avoid or resist, anything. Rather she just went her own way, following the dictates of her ear into what she calls her "tempered atonality." BTW, when you say that Stravinsky's Piano Concerto is an "almost laughably distorted version of his music, as he struggled to maintain a part of his identity within the strictures of the twelve tone system," though I don't agree with your characterization of it, you must have in mind his Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1960). Stravinsky's Piano Concerto (1924) is not a twelve-tone system work.

-

I admire Vivian Fine's music, but let's not put her in the "20th Century tonal composers" box, if that term implies, as it often tends to do, that the world of triadic tonal functions is a musical lost paradise that composers never should have left and to which, if they know what's good for them, they should return. Excerpts from an interview with Fine: Fine: During my teens. Ruth Crawford [later Ruth Crawford Seeger] was my first composition teacher. I heard her Violin Sonata no later than 1927, when I was 14 years old. It made a great impression on me, especially her freedom with string writing. I realize now that this sonata was influential, in that it gave me an idea of another kind of string sound besides the classical one, both in expression and technique. (I later recorded this piece with Ida Kavafian.) As a young composer I had to find my own way writing for instruments other than piano, because I didn’t have the opportunity to hear my compositions played. Later, when I was 17, I did hear a piece of mine for violin and piano performed at a student concert in Chicago; I think it was influenced by the very fine and somewhat neglected Sonatina by Carlos Chavez. I later revived the Crawford Sonata, at the Library of Congress. Both these works gave me a concept of modern string writing and the freedom to compose in a new way. Can you characterize what you mean by “modern” string writing? Fine: Well, it’s not like Vivaldi. Specifically, non-tonal. Didn’t you also have “older” sounds in your head from having studied piano? Usually young composers proceed in a conservative way, getting on the shoulders of the older composers and only gradually evolving a style or a voice of their own. Yet you set out to be “modern” as soon as you could. Fine: Almost from the beginning. The language of contemporary music was perfectly natural to me. Ruth Crawford was also a student of my piano teacher. Djane Lavoie-Herz, who had worked with Scriabin, and there was a Scriabinesque influence in some of her early works. Scriabin had actually left tonality and much of his harmony was built around fourths; that was the language I was used to.... Fine: From about 14 through 19, I did have a rather severely dissonant, atonal style. I didn’t use 12-tone techniques; I doubt I even knew about them, but I was familiar with atonal music, as I said, and I was severe as only young people can be severe. Then, in the mid-30s, there was a great shift in almost everyone’s music. Copland, for example, went from the modernism of his Piano Variations into his “American” style. It was part of a whole cultural and political manifestation, and my own music became quite tonal for a number of years. I was very involved with dance then and this tonal trend showed itself particularly in the ballets I wrote for Doris Humphreys and Charles Weidman. Then, in the mid-40s I turned to a style that was always anchored in some way to tonality, but not triadic tonality. I did admit a triad now and then, which would have been strictly forbidden in my earliest period! In these later years, then, you weren’t composing by avoidance, so to speak. Fine: No. And I think this tempered atonality has remained characteristic of my music. One listener referred to it as “mutating” tonality, which describes it very well, I think; the music veers off constantly into unaccustomed tonal relations. Another element that has remained constant in my music is its principally contrapuntal, linear approach. The harmonies fall where they fall; I hear them, but I rarely start out with a harmonic scheme.

-

As Jim Sangrey pointed out in that thread, my term "inventive fantasies" muchly exaggerates the differences between these charts and the Finegan and Sauter originals. When these versions sound different, I think it's mostly because of the album's brighter "hi-fi" engineering versus the more mellow homogenous sound of the original recordings.

-

Sorry -- all I've heard is Vol. 6.

-

What Classical Music Are You Listening To?

Larry Kart replied to StarThrower's topic in Classical Discussion

Admirer of Walker's music. A good deal of it can be found on the Albany label, often at Berkshire. -

Which Mosaic Are You Enjoying Right Now?

Larry Kart replied to Soulstation1's topic in Mosaic and other box sets...

Jimmy Raney. -

All the Noto Xanadu albums are worthwhile IMO. I particularly like the one with Sam Most in the frontline. Henderson influenced a lot of players. Back in his Jones-Lewis Orchestra days, Rich Perry (now very much his own man) was known as "Little Joe."

-

Shearing and the Adderley Bros. Newport 1957

Larry Kart replied to Larry Kart's topic in Recommendations

Glad you liked it. That it even existed was a surprise to me, -

Benny Goodman/Buddy Rich V-Disc 1947: Allen Eager (with Rich) has a very nice solo at 7:36:

-

Buddy Rich 1948. Outrageous.

-

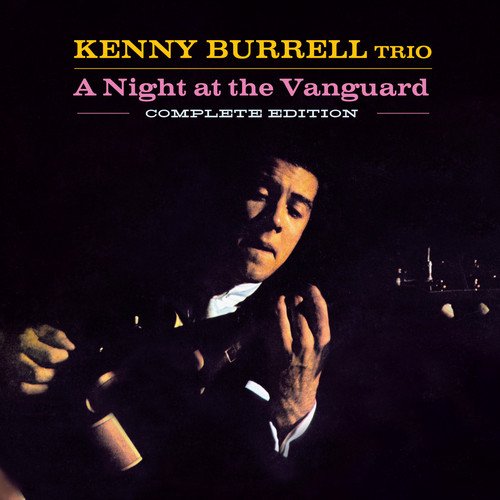

KB is in very fine form, and what a bass and drum team Richard Davis and Roy Haynes are. BTW, the "Complete Edition" has four more tracks.

_forumlogo.png.a607ef20a6e0c299ab2aa6443aa1f32e.png)